Myth and Mending on the Far Side of America

An interview with historian Betsy Gaines Quammen

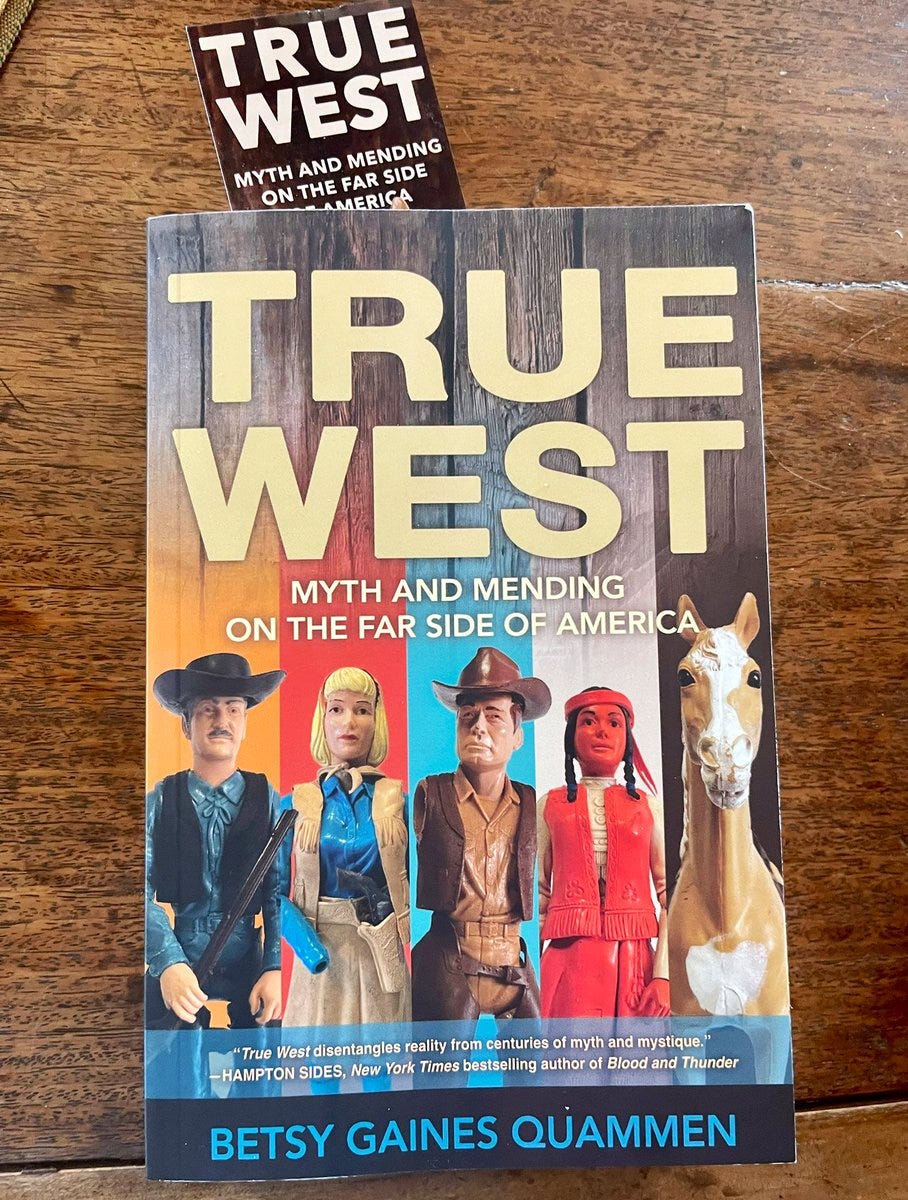

The American West is many things, but too many of our ideas about what it is and who lives here stray far from reality. Historian Betsy Gaines Quammen, who is based in Bozeman, Montana, has a new book out today unraveling some of our most persistent myths about the West and offering hope that our divisions can be repaired.

I talked with Betsy about her work and what led to “True West: Myth and Mending on the Far Side of America.” It’s a riveting book, a journey around the American West, in all of its characters, flaws and beauty. You can buy the book here: True West. If you happen to be in Missoula, we’ll be talking about all of this on Nov. 30 at the University of Montana as well.

Q: What led you to investigate "myth and mending" in the American West?

So many things! I was watching the country react to Covid and started to see how the West was impacted by people who came to view this region as an opportunity, a blank slate, a frontier, a refuge—the myths that have been around since settler colonialism. There are many misunderstandings brought by people coming here, which again, saddle the West with untenable expectations.

In the last couple of years, people moved to the intermountain states seeking more lax Covid regulations, with ideas that the West is as much a libertarian paradise as a salubrious “wilderness retreat.” Tourists came to visit, swamping small medical facilities in towns like Moab, UT and Ketchum, ID. I interviewed a book club in Blaine County, home to Ketchum, Hailey, and Sun Valley—one member was the first to die of Covid in that county, and another the last person to die.

In addition to Covid refugees, people moved to places like my town of Bozeman, many sight unseen, bringing with them characterizations from the television show Yellowstone, a melodrama of cringy stereotypes and sweeping vistas. They came, and continue to come, seeking this cartoon lifestyle as housing prices skyrocket, infrastructure is stressed, and community bonds loosen. Since 2019, Bozeman’s population has increased by 16.8%--nearly ten thousand new people moved here. Kathleen, you wrote about the young father to be, Sean Hawksford, with his sandwich board on Main Street, asking for someone to sell him a house. He managed to buy one. You also covered the growing number of RVs parked on empty roads—awaiting housing developments—that people are living in without hook-ups. So you know well the situation many communities are facing. Of course it isn’t just a western problem, but here, people are seduced by certain mythologies.

This is not all happening because of Kevin Costner and Covid. I write in True West about other western communities and the different myths that motivate migration. The Idaho Panhandle has lured Christian Nationalists gathering to build likeminded communities, pushing the state ever deeper into political redness. These extremist movements have been in the works for ages, via different iterations. I’m talking about Bo Gritz’s Almost Heaven, the Order, and Aryan Nations that have targeted Idaho as a bastion. Myths of homeland.

I kept bumping into people lured by myth. I met a gal who moved to eastern Montana, chasing the agrarian myth, the story long ago peddled by those promising rain follows the plow. She came seeking refuge from the evils that QANON warned her about, living on her in-laws’ farm, raising vaxxed lambs and unvaxxed kids.

This myth of the West as a playground drew still more folks with mountain bikes, skis, and Sprinter vans. I explore how recreationalist and selfie culture stand in stark contrast to Indigenous ways of regarding their sacred lands that became designated as national parks, monuments, and wilderness areas. The contrast led me to the further investigation of Judeo-Christian notions of duality, land commodification, and the biblical call to subdue the Earth. Extractive practices, like mining, agriculture, and extreme recreation have impacted our geography and culture. These industries, with their booms and busts, deeply affected economics and politics, for better and for worse. And these cycles, of course, defined western communities and supported the working class. Now, with timber and mining in the bust phase of the boom-and-bust cycle, high end luxury tourism has focused on wealthy outsiders who more and more build exclusive and gilded sanctuaries into ever shrinking wildland and wildlife habitats, causing greater inequities, water pollution, and diminishing community cohesion as wealthy transients only seasonally occupy properties. There are jobs associated with high-end brick and mortar projects, but the service industry jobs offer paltry wages.

I set out to understand how all of this was tangled together: myth, politics, pandemic reverberations, economics, and misinformation. Then I looked for ways to get back into relationship with one another as we tackle the tangle.

Q: In your research, what did you learn about the West that surprised you?

That there are many people who have deep and abiding affinity for this place. This might be most evident in the ongoing Native resistance movement. There have been intentional campaigns to negate the existence of Native people—both through genocide and by the erasure of their cultures through assimilation—but resistance movements are stronger that ever. This is not a surprise, as much as it is a thrill to see. I’ve watched some of this as conservation organizations come to terms with white, colonialist history. I write about an organization in New Mexico navigating this history.

As far as surprises go, what really did surprise me were the Republican activists in Idaho fighting to save their party from the clutches of America First, Nick Fuentes’s group, and the increasing radicalization brought in part by American Redoubt culture. I wasn’t surprised to see Idaho Republicans fighting as much as I was buoyed by Republicans in the state having more courage and being more effective than national players.

Communities traditionally tied to resource extraction—former mining and logging communities that struggle to fight gentrification and create good jobs with living wages—have become targets for extremists looking for support in these communities angry over the collapse of extractive jobs. Old sawmill towns have been seized by militants, religious radicals, and racists. North Idaho has a long history of attracting extremists, and communities there have historically fought back. Now we are seeing folks in Sand Point, Coeur D’Alene, and Bonner’s Ferry fight hate groups coming to LGBTQ events, beat back Christian nationalists trying to infiltrate school boards and defund public schools, and push against other forms of extremism. In the 1990s, this was the frontline in the battle against Richard Butler and Aryan Nations. Now we are seeing a fight against American Redoubt, a movement encouraging migration to Idaho (among other western states) to establish a refuge for anti-government agitators. These folks have joined up with the ultra-right Idaho Freedom Foundation, a confrontational organization, who have supported folks like Ammon Bundy and former lieutenant governor Janice McGeachin, an ardent fan of the militia group, the Real Three Percent of Idaho.

Q: We in the West tend to be seen as living in, as K Ross Toole said of Montana, "a state of extremes." Where did you find common ground among Westerners? Is there hope that can be expanded?

We are a region of extremes, but until fairly recently, places like the state of Montana were purple. I still think it’s possible to sort through the garbage that’s been foisted on us, from lies about socialism proliferated by John Birch types, to stuff we’ve created ourselves, like mistrust between urban and rural westerners.

This is a book about relationship building, among neighbors, community members, and rural and urban populations. I was pleasantly surprised at how, in many cases, people were ready to re-examine resentment and connect. Despite what we are told on media, by cynical politicians, and by organizations intent on destabilizing democratic institutions and our society, people want to connect and find common ground. We can protect our communities from toxic myth, the proliferation of misinformation, and those—be they politicians, political operatives, shit stirrers, or high end developers—who do not have our best interests at heart, only when we are in relationship with one another.

Q: What do you hope people take away from this book when they read it?

True West makes the point that the West, its myths as much as its geography, defines America. Western mythology is baked into the very notion of American character. The book tries to illuminate what is true about the American West, in contrast to all the things people tend to believe about the West that aren’t true. We live in a time of competing myths. True West navigates western mythology, thereby American mythology, untangling falsehood from reality so that we can be clear, we can heal, we can build relationships, and we can reconnect in a country that often feels like it’s being torn apart.

The other thing I hope people take away from the book is sheer enjoyment at my guided tour through some little-visited rooms in this great, fraught, wondrous galleries of myths and realities we call the West.

What a good interview and I’m really looking forward to reading this book! Here’s to everyone fighting colonialism and oppression in all its forms.

I've never lived in the west but only visited friends and relatives. The south has its own set of toxic myths. I suppose every place does.